Inside Farfetch’s Bid to Dominate Luxury E-Commerce

By Robert Williams and Tamison O’Connor

During a blockbuster year for online sales, Farfetch surged ahead of rivals to position

itself at the front of luxury’s e-commerce race. Can it spin the current momentum

into sustainable — and profitable — growth and become the unrivalled platform for

luxury fashion online?

During a blockbuster year for online sales, Farfetch surged ahead of rivals to position

itself at the front of luxury’s e-commerce race. Can it spin the current momentum

into sustainable — and profitable — growth and become the unrivalled platform for

luxury fashion online?

Executive Summary

A year ago, the biggest players in luxury e-commerce faced an uncertain future. Myriad competitors had flooded a space once dominated by Net-a-Porter, ranging from vast marketplace Farfetch to niche challengers like MyTheresa, MatchesFashion and Ssense. These sites were largely undifferentiated, often selling the same products at the same price, while offering similar customer experiences. That led to high marketing costs, frequent promotions and difficulties reaching the necessary scale to pay off significant investments in technology, logistics, rapid shipping and other white-glove services.

At the same time, luxury brands were ramping up their own e-commerce stores and shoppers were flocking to social media platforms like Instagram for style advice and product curation, eliminating much of the need to digitise the traditional multi-brand retail model. “They’re all losing money. It’s not a good sign,” LVMH chairman Bernard Arnault said in a January 2020 presentation, commenting on the challenges faced by his company’s own multi-brand e-commerce venture, 24S.

“The bigger they get, the more money they lose.” One player in particular faced an uphill battle to reassure investors about its future: Farfetch, the marketplace founded and led by José Neves, which had made a name for itself by short-circuiting luxury brands who were slow to enter e-commerce. Instead of relying on the brands for stock, he had created a platform for multi-brand boutiques around the world to sell their inventories online. A year after raising $885 million in a much-hyped initial public offering, Farfetch faced mounting concerns about its lack of profitability and high costs for acquiring clients. Market support collapsed following an unexpected move to acquire Milanese streetwear manufacturer New Guards Group, and by the autumn of 2019.

A year ago, the biggest players in luxury e-commerce faced an uncertain future. Myriad competitors had flooded a space once dominated by Net-a-Porter, ranging from vast marketplace Farfetch to niche challengers like MyTheresa, MatchesFashion and Ssense. These sites were largely undifferentiated, often selling the same products at the same price, while offering similar customer experiences. That led to high marketing costs, frequent promotions and difficulties reaching the necessary scale to pay off significant investments in technology, logistics, rapid shipping and other white-glove services.

At the same time, luxury brands were ramping up their own e-commerce stores and shoppers were flocking to social media platforms like Instagram for style advice and product curation, eliminating much of the need to digitise the traditional multi-brand retail model. “They’re all losing money. It’s not a good sign,” LVMH chairman Bernard Arnault said in a January 2020 presentation, commenting on the challenges faced by his company’s own multi-brand e-commerce venture, 24S.

“The bigger they get, the more money they lose.” One player in particular faced an uphill battle to reassure investors about its future: Farfetch, the marketplace founded and led by José Neves, which had made a name for itself by short-circuiting luxury brands who were slow to enter e-commerce. Instead of relying on the brands for stock, he had created a platform for multi-brand boutiques around the world to sell their inventories online. A year after raising $885 million in a much-hyped initial public offering, Farfetch faced mounting concerns about its lack of profitability and high costs for acquiring clients. Market support collapsed following an unexpected move to acquire Milanese streetwear manufacturer New Guards Group, and by the autumn of 2019.

Farfetch shares were trading at less than 40 percent of their IPO price. Fast-forward to a year later and the coronavirus pandemic has driven a luxury e-commerce boom. Amid a freeze in long-haul tourism and the intermittent closures of physical boutiques due to coronavirus containment measures, e-commerce has scooped up an unprecedented share of luxury demand. Farfetch enjoyed the most dramatic turnaround.

Its market capitalisation grew by a whopping 475 percent in 2020 — more than other companies that experienced a notable pandemic boom, like vaccine-maker BioNTech (whose shares went up 125 percent) or home cycling hit Peloton (up 432 percent). Neves has said the company will report positive EBITDA (a measure of profit) for the first time ever for the fourth quarter of 2020. Last November, the company inked a blockbuster deal aimed at accelerating its expansion in China — already the growth driver for luxury and more important than ever following the country’s comparatively swift economic recovery.

The partnership signed with Chinese e-commerce giant Alibaba and Swiss luxury group Richemont (alongside Pinault family holding company Artémis) raised $1.1 billion and has pushed excitement about the company to new heights. Investors are now betting that Farfetch will not only become profitable, but that it can fulfil its mission to become the world’s go-to marketplace for high-end fashion, “connecting creators, curators and consumers.” In short, they’re betting it can be the so-called Amazon of luxury. “If not them, who else could be?” Cowen analyst Oliver Chen said. In our April 2020 case study, “The Next Wave of Luxury E-Commerce,” The Business of Fashion explored the rise of Yoox Net-a-Porter (YNAP) and how its dominant position in online luxury gradually eroded amid mounting competition from brands’ own websites, marketplaces like Farfetch and niche online boutiques with devoted followings.

Now, we take a closer look at Farfetch, and how it has seized the pandemic opportunity in luxury e-commerce to surge ahead. The value of products sold on its marketplace grew by nearly 50 percent during coronavirus lockdowns in the spring of 2020, and are now close to overtaking the sales of chief rival Net-a-Porter. Looking ahead, how strong is Farfetch’s advantage in the luxury e-commerce race? A $21 billion market capitalisation certainly sets it apart from the pack. But can Farfetch buck the trend of luxury brands moving to more direct relationships with consumers, both online and off — a strategic shift which risks cutting out multi-brand players? And how will it fend off the challenge from technology giants like Amazon, which is redoubling its efforts to break into selling luxury fashion, or Alibaba, which has invested in Farfetch even as its own high-end venture, the Tmall Luxury Pavilion, continues to gain ground?

We’ll understand what makes Farfetch stand out to investors, including its marketplace model and technology investments, and how fashion brands’ increased appetite for its services allowed it to stage a spectacular comeback in the market and nab a historic deal.

Its market capitalisation grew by a whopping 475 percent in 2020 — more than other companies that experienced a notable pandemic boom, like vaccine-maker BioNTech (whose shares went up 125 percent) or home cycling hit Peloton (up 432 percent). Neves has said the company will report positive EBITDA (a measure of profit) for the first time ever for the fourth quarter of 2020. Last November, the company inked a blockbuster deal aimed at accelerating its expansion in China — already the growth driver for luxury and more important than ever following the country’s comparatively swift economic recovery.

The partnership signed with Chinese e-commerce giant Alibaba and Swiss luxury group Richemont (alongside Pinault family holding company Artémis) raised $1.1 billion and has pushed excitement about the company to new heights. Investors are now betting that Farfetch will not only become profitable, but that it can fulfil its mission to become the world’s go-to marketplace for high-end fashion, “connecting creators, curators and consumers.” In short, they’re betting it can be the so-called Amazon of luxury. “If not them, who else could be?” Cowen analyst Oliver Chen said. In our April 2020 case study, “The Next Wave of Luxury E-Commerce,” The Business of Fashion explored the rise of Yoox Net-a-Porter (YNAP) and how its dominant position in online luxury gradually eroded amid mounting competition from brands’ own websites, marketplaces like Farfetch and niche online boutiques with devoted followings.

Now, we take a closer look at Farfetch, and how it has seized the pandemic opportunity in luxury e-commerce to surge ahead. The value of products sold on its marketplace grew by nearly 50 percent during coronavirus lockdowns in the spring of 2020, and are now close to overtaking the sales of chief rival Net-a-Porter. Looking ahead, how strong is Farfetch’s advantage in the luxury e-commerce race? A $21 billion market capitalisation certainly sets it apart from the pack. But can Farfetch buck the trend of luxury brands moving to more direct relationships with consumers, both online and off — a strategic shift which risks cutting out multi-brand players? And how will it fend off the challenge from technology giants like Amazon, which is redoubling its efforts to break into selling luxury fashion, or Alibaba, which has invested in Farfetch even as its own high-end venture, the Tmall Luxury Pavilion, continues to gain ground?

We’ll understand what makes Farfetch stand out to investors, including its marketplace model and technology investments, and how fashion brands’ increased appetite for its services allowed it to stage a spectacular comeback in the market and nab a historic deal.

From Hype to Slump to Pandemic Surge

In the lead-up to its public listing, Farfetch was touted as one of the most exciting start-ups in luxury and e-commerce. Launched in 2007, the brainchild of Portuguese entrepreneur José Neves, London-based Farfetch aimed to disrupt the luxury e-commerce space by circumventing the key weakness in the traditional wholesale model adopted by the first generation of luxury e-commerce players — the risk of buying and holding product — by instead devising a zero-inventory system for sourcing products from the stock of multi-brand boutiques around the world, many of whom were willing to forfeit a commission in exchange for the chance to reach a global audience online.

Farfetch did the heavy lifting of compiling coherent product imagery and accurate descriptions, building up an extensive digital catalogue of luxury products, while wholesale partners benefitted from an additional channel for moving inventory without diverting bandwidth and resources from their brick-and-mortar business. Farfetch was also able to focus on honing its logistical prowess, refining systems to host huge databases of product information, monitor the inventories of brick-and-mortar partners, and ensure speedy customs clearing and delivery for international orders and returns.

Farfetch did the heavy lifting of compiling coherent product imagery and accurate descriptions, building up an extensive digital catalogue of luxury products, while wholesale partners benefitted from an additional channel for moving inventory without diverting bandwidth and resources from their brick-and-mortar business. Farfetch was also able to focus on honing its logistical prowess, refining systems to host huge databases of product information, monitor the inventories of brick-and-mortar partners, and ensure speedy customs clearing and delivery for international orders and returns.

While older rival Net-a-Porter had worked up a strong reputation for product selections, storytelling and white-glove service — all qualities that endeared the site to brands as well as clients — investors saw the potential for Farfetch to scale up rapidly and overtake the market leader. Farfetch was a textbook example of a “platform” business: one which, like Airbnb, positions itself as a facilitator, connecting supply and demand, rather than the more traditional “pipe” business model, which relies on pushing merchandise from producer to consumer. Luxury brands, known for strictly guarding their public images, were not always happy to see products they had sold to brick-and-mortar wholesalers readily for sale on Farfetch — online and outside of their control. But for every brand that snubbed the site — like Celine, which banned its wholesale stockists from selling its bags or ready-to-wear there — others got in line to support Neves’ vision.

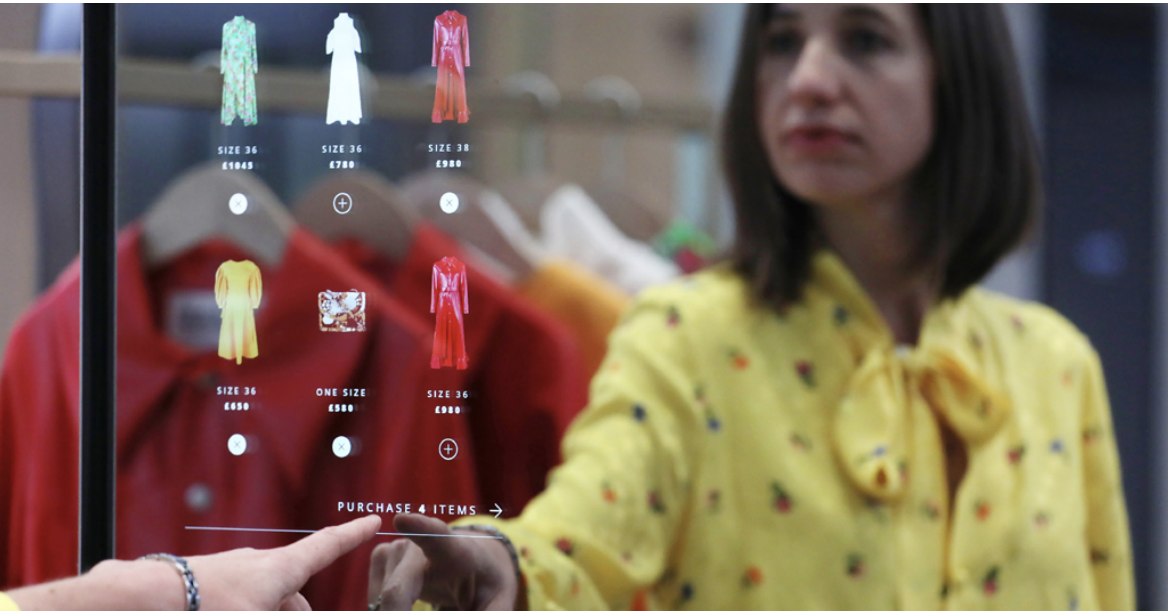

Early financial backers (some of which have since sold their shares) included Vogue publisher Condé Nast, the Pinault family holding company Artémis (which controls luxury group Kering with its Gucci and Saint Laurent brands), Eurazeo (the private equity company that backed Moncler and Desigual) and Chanel. The influx of cash from well-known sources gave Farfetch both industry credibility and significant financial resources, which it poured into developing various tools and services, often launched in partnership with big-name brands, from 90-minute delivery (Gucci) to in-store “augmented retail” technology (Chanel). However, the scale of those investments, as well as high marketing costs, divided opinion. If the Farfetch model was so good, why were they losing so much money?

Doubters wondered whether the services and technologies Farfetch was developing were frivolous, and if the market opportunity was really big enough for the company to recoup its investments. Nonetheless, when Farfetch debuted on the New York Stock Exchange in September 2018 following a much-hyped roadshow pitching the idea to investors, its initial public offering was an undeniable success. Shares shot up nearly 50 percent over the IPO price on the first day of trading, pushing the platform’s valuation past $8 billion. But soon investors realised that, in addition to the expense of developing tech prowess and providing luxury delivery services, the site was contending with much the same environment of price competition and rampant discounting as online wholesalers.

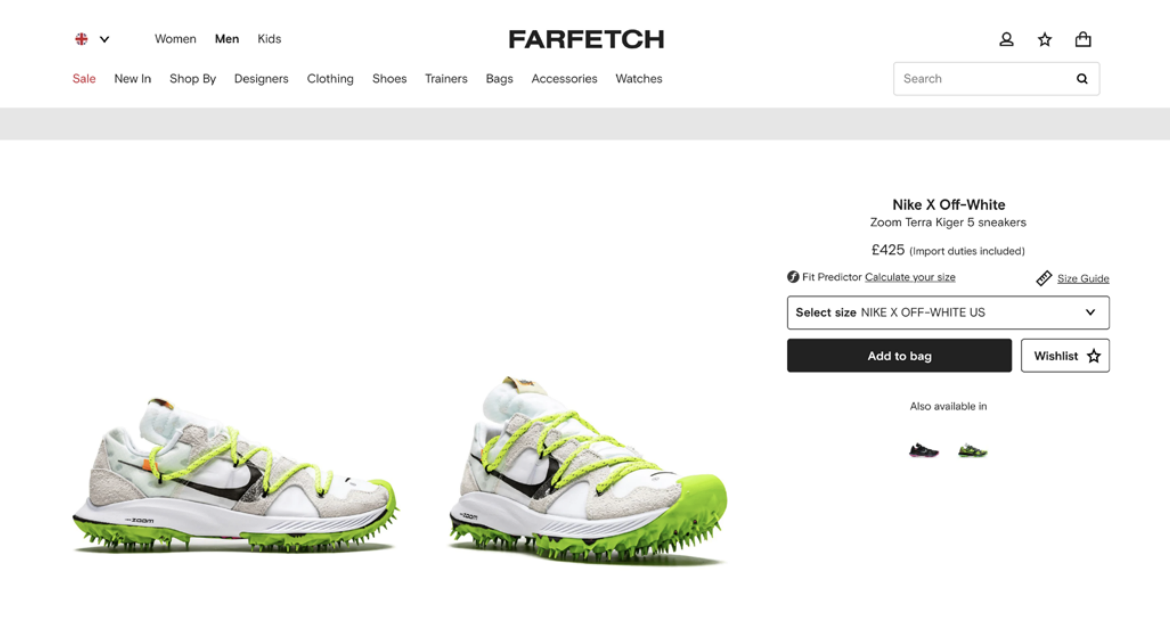

The company’s mounting losses weren’t just attributable to tech investments, but also to the marketing expenses required to acquire each customer — via discounts and expensive placements in search directories like Google Shopping. Then, the market value of the company ebbed further in August 2019 after it acquired New Guards Group (NGG), a Milanese sourcing and distribution hub for luxury streetwear brands that it owns or operates as a licensee (depending on the label) for the likes of Virgil Abloh’s Off-White, Palm Angels and Heron Preston. The group was profitable, and its brands were red hot — but investors weren’t thrilled.

“The shareholder base found themselves owning brands instead of a platform. It just wasn’t in their expectations,” said Oliver Chen, analyst at Cowen. The value of the company’s shares tumbled 44 percent in one day from $18.25 to $10.13. Neves defended the NGG acquisition as an accelerator for creative brands — Farfetch would provide the labels with a platform to grow more quickly, while the site gained access to exclusive content and product launches to help differentiate itself in a crowded streetwear market.

“We think this is an incredible acceleration of our existing strategy,” Neves said. The company persisted in its spirit of experimental moves, adding a second-hand clothing service, acquiring the peer-to-peer sneaker site Stadium Goods, and adding Ambush and Opening Ceremony to its NGG stable. Farfetch wasn’t the only player in the market facing troubles: its biggest competitor Net-a-Porter turned loss-making in 2019, according to a UK company filing, with parent company Richemont citing a promotional climate and a fraught migration to a new technology system as dragging down its multi-brand e-commerce activities. Smaller rival MatchesFashion also found itself overstretched, with full-price sales...

Early financial backers (some of which have since sold their shares) included Vogue publisher Condé Nast, the Pinault family holding company Artémis (which controls luxury group Kering with its Gucci and Saint Laurent brands), Eurazeo (the private equity company that backed Moncler and Desigual) and Chanel. The influx of cash from well-known sources gave Farfetch both industry credibility and significant financial resources, which it poured into developing various tools and services, often launched in partnership with big-name brands, from 90-minute delivery (Gucci) to in-store “augmented retail” technology (Chanel). However, the scale of those investments, as well as high marketing costs, divided opinion. If the Farfetch model was so good, why were they losing so much money?

Doubters wondered whether the services and technologies Farfetch was developing were frivolous, and if the market opportunity was really big enough for the company to recoup its investments. Nonetheless, when Farfetch debuted on the New York Stock Exchange in September 2018 following a much-hyped roadshow pitching the idea to investors, its initial public offering was an undeniable success. Shares shot up nearly 50 percent over the IPO price on the first day of trading, pushing the platform’s valuation past $8 billion. But soon investors realised that, in addition to the expense of developing tech prowess and providing luxury delivery services, the site was contending with much the same environment of price competition and rampant discounting as online wholesalers.

The company’s mounting losses weren’t just attributable to tech investments, but also to the marketing expenses required to acquire each customer — via discounts and expensive placements in search directories like Google Shopping. Then, the market value of the company ebbed further in August 2019 after it acquired New Guards Group (NGG), a Milanese sourcing and distribution hub for luxury streetwear brands that it owns or operates as a licensee (depending on the label) for the likes of Virgil Abloh’s Off-White, Palm Angels and Heron Preston. The group was profitable, and its brands were red hot — but investors weren’t thrilled.

“The shareholder base found themselves owning brands instead of a platform. It just wasn’t in their expectations,” said Oliver Chen, analyst at Cowen. The value of the company’s shares tumbled 44 percent in one day from $18.25 to $10.13. Neves defended the NGG acquisition as an accelerator for creative brands — Farfetch would provide the labels with a platform to grow more quickly, while the site gained access to exclusive content and product launches to help differentiate itself in a crowded streetwear market.

“We think this is an incredible acceleration of our existing strategy,” Neves said. The company persisted in its spirit of experimental moves, adding a second-hand clothing service, acquiring the peer-to-peer sneaker site Stadium Goods, and adding Ambush and Opening Ceremony to its NGG stable. Farfetch wasn’t the only player in the market facing troubles: its biggest competitor Net-a-Porter turned loss-making in 2019, according to a UK company filing, with parent company Richemont citing a promotional climate and a fraught migration to a new technology system as dragging down its multi-brand e-commerce activities. Smaller rival MatchesFashion also found itself overstretched, with full-price sales...

could ship out orders from somewhere else that was less impacted. Being able to source products not just from warehouses, but also from shop floors at boutiques around the world, meant the company had a high degree of flexibility built into its marketplace. As long as one stockist somewhere in the world was able to access and ship a given SKU, a customer could still order it on the site. Even though overall luxury demand was lower during the early stages of the pandemic, a large share of the remaining demand went to Farfetch as it was one of the only global retailers to continue operations. In the quarter ending June 30, the value of products sold on Farfetch rose 48 percent year-on-year, hitting $651 million, while site traffic was up 60 percent.

Over the summer, the surge continued with the value of products sold rising 60 percent in the quarter ending September 30. Now the company is closing in on the market leader, YNAP. The value of products sold by Farfetch’s core digital division amounted to $2.3 billion in the 12 months ending September 30, 2020, while sales at Richemont’s online distributors division, which owns YNAP, were only marginally higher at $2.6 billion, according to analysis by Cowen. Taking its New Guards Group business into account, the size of Farfetch’s overall business surpassed that of YNAP last June.

Over the summer, the surge continued with the value of products sold rising 60 percent in the quarter ending September 30. Now the company is closing in on the market leader, YNAP. The value of products sold by Farfetch’s core digital division amounted to $2.3 billion in the 12 months ending September 30, 2020, while sales at Richemont’s online distributors division, which owns YNAP, were only marginally higher at $2.6 billion, according to analysis by Cowen. Taking its New Guards Group business into account, the size of Farfetch’s overall business surpassed that of YNAP last June.

02 — Improving Traction With Brands

During its early years, executives at some brands saw Farfetch’s model as cynical and even sneaky, particularly those that had been deliberately avoiding e-commerce out of concern that growing online accessibility for luxury goods would dilute their brands. But Farfetch, by tapping into the inventories of the brands’ brick-and-mortar stockists, was putting their products for sale online anyway. Brands could not control the product offering, how the products were presented, or at what price. Some wariness of the platform has persisted: during the coronavirus pandemic, independent brands have complained that steep discounts on Farfetch created waves of early markdowns on other sites. (Farfetch maintains that discounting on its platform is outside its control, since brands and retailers participating in the marketplace set their own prices.)

Still, for every brand that has fought to avoid Farfetch, plenty of others have lined up to work with the company, and this means Farfetch’s B2B business is accelerating on multiple fronts. Concessions: As of October 2020, 550 fashion brands operate concessions on Farfetch’s marketplace, compared to fewer than 400 brands in 2018. The concession model enables brands to post their products for sale directly to the site, in addition to fulfilling orders from wholesale boutiques. Farfetch’s systems can tap into inventories located at brands’ stores in addition to warehouses — enabling flexible order fulfilment. Prada, for example, has given Farfetch access to 70 inventory points, allowing for same-day delivery in 20 cities.

At one point, access to inventory was a serious concern for Farfetch as major brands like Prada, Burberry and Gucci began to shift away from wholesale, emulating the strictly controlled, retail-only model of Louis Vuitton and Hermès. Concessions have plugged that gap for now. For brands, selling on Farfetch helps make up for lost wholesale revenues, while appealing to their desire to control pricing and selection in real time. Farfetch’s commission can also be financially attractive when compared to the discounts at which brands sell to wholesalers. Farfetch’s average “take rate” was 30 percent in the third quarter of 2020, but this varies among brands and retailers. Some of the strongest brands pocket as much as 80 to 85 percent of the price they would get at retail selling on Farfetch, compared to 40 to 50 percent selling wholesale, according to a report from Bernstein.

Shared Technologies: Farfetch has also deepened ties with brands and retailers by launching its “Platform Solutions” division (previously called Black and White) as a business-to-business offer where brands pay to use Farfetch’s technologies and logistics network to power their own operations on the back-end. First launched in 2015, it now counts 22 brands as clients including Thom Browne and Ami Paris. Thom Browne opted for Farfetch’s systems as it tries to shift from wholesale to a more direct-to-consumer model, working with the site to integrate online and offline services like booking store appointments, offering video chats with sales associates, and maintaining greater visibility of global product availability in each of its relatively small boutiques.

Farfetch also worked with Harrods on its new e-commerce website, devising a system to offer items from its owned inventory alongside items from brands that are operating inside the department store as a shop-in-shop concession. Orders can be filled from a concession on the Harrods floor and shipped out in a Harrods box, with customers none the wiser that the order used Farfetch’s systems for e-commerce, payment, customs clearing and delivery on the back-end. The department store is also testing an “online concession” model in which brands could propose a more extensive inventory on Harrods.com and ship orders from their own warehouses. Farfetch is hardly the only company to be developing white-label technology for e-commerce, be it in chat support.

Still, for every brand that has fought to avoid Farfetch, plenty of others have lined up to work with the company, and this means Farfetch’s B2B business is accelerating on multiple fronts. Concessions: As of October 2020, 550 fashion brands operate concessions on Farfetch’s marketplace, compared to fewer than 400 brands in 2018. The concession model enables brands to post their products for sale directly to the site, in addition to fulfilling orders from wholesale boutiques. Farfetch’s systems can tap into inventories located at brands’ stores in addition to warehouses — enabling flexible order fulfilment. Prada, for example, has given Farfetch access to 70 inventory points, allowing for same-day delivery in 20 cities.

At one point, access to inventory was a serious concern for Farfetch as major brands like Prada, Burberry and Gucci began to shift away from wholesale, emulating the strictly controlled, retail-only model of Louis Vuitton and Hermès. Concessions have plugged that gap for now. For brands, selling on Farfetch helps make up for lost wholesale revenues, while appealing to their desire to control pricing and selection in real time. Farfetch’s commission can also be financially attractive when compared to the discounts at which brands sell to wholesalers. Farfetch’s average “take rate” was 30 percent in the third quarter of 2020, but this varies among brands and retailers. Some of the strongest brands pocket as much as 80 to 85 percent of the price they would get at retail selling on Farfetch, compared to 40 to 50 percent selling wholesale, according to a report from Bernstein.

Shared Technologies: Farfetch has also deepened ties with brands and retailers by launching its “Platform Solutions” division (previously called Black and White) as a business-to-business offer where brands pay to use Farfetch’s technologies and logistics network to power their own operations on the back-end. First launched in 2015, it now counts 22 brands as clients including Thom Browne and Ami Paris. Thom Browne opted for Farfetch’s systems as it tries to shift from wholesale to a more direct-to-consumer model, working with the site to integrate online and offline services like booking store appointments, offering video chats with sales associates, and maintaining greater visibility of global product availability in each of its relatively small boutiques.

Farfetch also worked with Harrods on its new e-commerce website, devising a system to offer items from its owned inventory alongside items from brands that are operating inside the department store as a shop-in-shop concession. Orders can be filled from a concession on the Harrods floor and shipped out in a Harrods box, with customers none the wiser that the order used Farfetch’s systems for e-commerce, payment, customs clearing and delivery on the back-end. The department store is also testing an “online concession” model in which brands could propose a more extensive inventory on Harrods.com and ship orders from their own warehouses. Farfetch is hardly the only company to be developing white-label technology for e-commerce, be it in chat support.

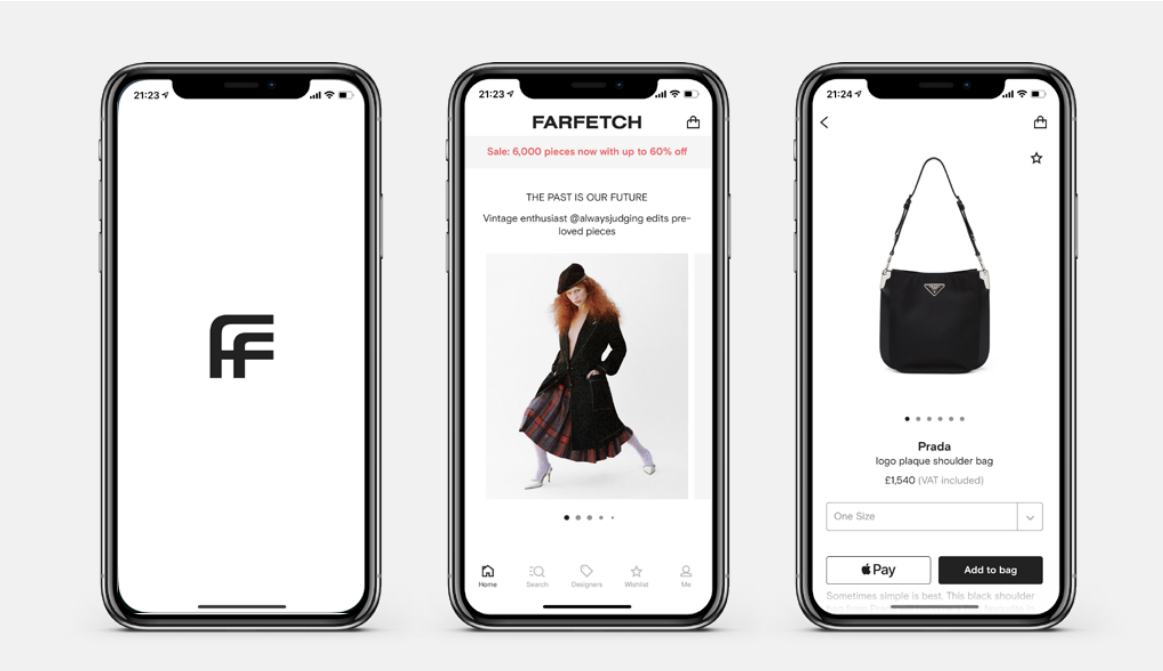

03 — Progress on Branding and Differentiation

Farfetch has struggled to become a big and sufficiently aspirational brand name in line with the company’s ambition to become the go-to site for ordering luxury products. Neves himself has acknowledged Farfetch is “a bigger business than it is a brand.” While Farfetch’s far-reaching selection is central to its strategy, that can also make it difficult to develop the kind of focused brand proposition built by curated retailers, which carefully manage the selection of specific products to carve out a strong identity. Ssense, MatchesFashion and MyTheresa are among the sites to pride themselves on a strict “edit” to appeal to a specific client base.

Consumers reward those sites for presenting them with fewer, but more pertinent options, giving them repeat business which drives up the average lifetime value of customers. As a marketplace, Farfetch can’t control its selection in the same way. But the company has been making an effort to raise the awareness and positioning of the Farfetch brand. Farfetch named Holli Rogers, former Net-a-Porter fashion director and CEO of Farfetch’s Browns boutique, to serve as its chief brand officer in 2019. In September 2020, Farfetch unveiled a rebrand for its website, launching its first global advertising campaign across print, social

Consumers reward those sites for presenting them with fewer, but more pertinent options, giving them repeat business which drives up the average lifetime value of customers. As a marketplace, Farfetch can’t control its selection in the same way. But the company has been making an effort to raise the awareness and positioning of the Farfetch brand. Farfetch named Holli Rogers, former Net-a-Porter fashion director and CEO of Farfetch’s Browns boutique, to serve as its chief brand officer in 2019. In September 2020, Farfetch unveiled a rebrand for its website, launching its first global advertising campaign across print, social

media, outdoor advertising and television. The campaign featured editorial shoots by fashion photographer Harley Weir and styled by Lotta Volkova, and featured actor Jeremy O. Harris, environmentalist Wilson Oryema, poet Sonny Hall and actress Angelababy. It has also worked on leveraging its New Guards Group acquisition to offer exclusive drops for highly sought-after brands and products. A flood of new clients came to the site for the launch of a collaboration between its Off-White brand (licensed by NGG) and Nike, leading to the marketplace’s busiest-ever sales day.

Brand awareness is rising in the UK. The Farfetch brand was recognised by 41 percent of respondents in WGSN’s latest prompted brand recognition Barometer. But that’s still far behind Net-a-Porter, which was recognised by 66 percent of respondents in the study. Spending on customer acquisition has improved relative to sales, meaning the company may have hit an inflection point on the issue: in the second quarter of 2020, the value of products sold on the site increased by 48 percent, compared with a 38 percent year-over-year increase in the expenses Farfetch classifies as “demand generation” costs. In the third quarter, sales accelerated further, growing 60 percent while demand generation expenses increased by 35 percent.

Brand awareness is rising in the UK. The Farfetch brand was recognised by 41 percent of respondents in WGSN’s latest prompted brand recognition Barometer. But that’s still far behind Net-a-Porter, which was recognised by 66 percent of respondents in the study. Spending on customer acquisition has improved relative to sales, meaning the company may have hit an inflection point on the issue: in the second quarter of 2020, the value of products sold on the site increased by 48 percent, compared with a 38 percent year-over-year increase in the expenses Farfetch classifies as “demand generation” costs. In the third quarter, sales accelerated further, growing 60 percent while demand generation expenses increased by 35 percent.

04 — After Struggling to Break In, a New China Partnership

A prolonged freeze in international travel since the coronavirus first emerged in January has meant that Chinese clients are shopping domestically and shopping online more than ever. Farfetch first began operations in China in 2015, launching a .CN website the following year — and several years before the likes of Prada or Chanel. Today, the company has 450 employees across three offices in Beijing, Shanghai and Hong Kong. Early on, it struck key partnerships with Tencent and JD.com to gain traction in the market. But sales have still not taken off in line with the country’s importance to the luxury goods industry. “It did not ramp up as expected,” said Neves on a recent call with investors when asked about the deal with JD.com. “We have to make the very simple decision on how to best allocate our capital and resources.

” Now, Farfetch is hoping to change that with a new joint venture with Alibaba, which owns the country’s biggest online retailer, Tmall. In mid-2021, Farfetch is set to open shops on Tmall’s Luxury Pavilion, luxury outlet platform Luxury Soho and cross-border marketplace Tmall Global, giving Tmall’s over 750 million consumers easy access to Farfetch’s global selection of more than 3,000 brands. This includes many smaller luxury brands which have never managed to tackle the barriers to entry for selling in China, making them exclusive to the Chinese market — for now. Farfetch says it plans to source products for the Tmall concession from its global network of stockists the same way it does in other regions. The logistics system Farfetch has developed will allow the company to fulfil items from the global selection with delivery and returns lead times of three to four days on average, Neves said, including in China’s tier-three and -four cities.

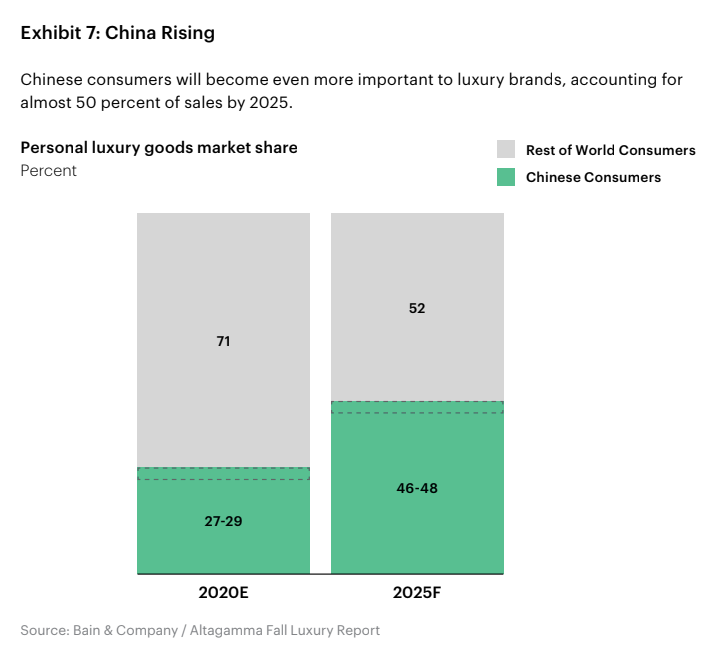

Chinese consumers were already accounting for 35 percent of consumption and the majority of growth in the luxury market in 2019, according to Bain, although much of that spending took place abroad. Thanks to reduced international travel, the repatriation of Chinese spending has accelerated. Farfetch estimates that China’s domestic luxury market alone is now a $70 billion opportunity.

” Now, Farfetch is hoping to change that with a new joint venture with Alibaba, which owns the country’s biggest online retailer, Tmall. In mid-2021, Farfetch is set to open shops on Tmall’s Luxury Pavilion, luxury outlet platform Luxury Soho and cross-border marketplace Tmall Global, giving Tmall’s over 750 million consumers easy access to Farfetch’s global selection of more than 3,000 brands. This includes many smaller luxury brands which have never managed to tackle the barriers to entry for selling in China, making them exclusive to the Chinese market — for now. Farfetch says it plans to source products for the Tmall concession from its global network of stockists the same way it does in other regions. The logistics system Farfetch has developed will allow the company to fulfil items from the global selection with delivery and returns lead times of three to four days on average, Neves said, including in China’s tier-three and -four cities.

Chinese consumers were already accounting for 35 percent of consumption and the majority of growth in the luxury market in 2019, according to Bain, although much of that spending took place abroad. Thanks to reduced international travel, the repatriation of Chinese spending has accelerated. Farfetch estimates that China’s domestic luxury market alone is now a $70 billion opportunity.

Looking Ahead

Luxury e-commerce growth will inevitably slow in 2021. But digital buying habits won’t be unlearned, and demand for online luxury fashion is expected to stick well above pre-pandemic levels and continue to grow mid-term. Investors are betting on Farfetch as the luxury e-commerce player best positioned to seize that opportunity. But Farfetch will need to remain agile as the hyper-competitive multi-brand e-commerce space continues to consolidate. Even if it manages to pull ahead of its rivals, the ambitions of much larger players from the broader world of e-commerce and technology could come into play. To maintain the support of investors, Farfetch needs to deliver on its profitability promise.

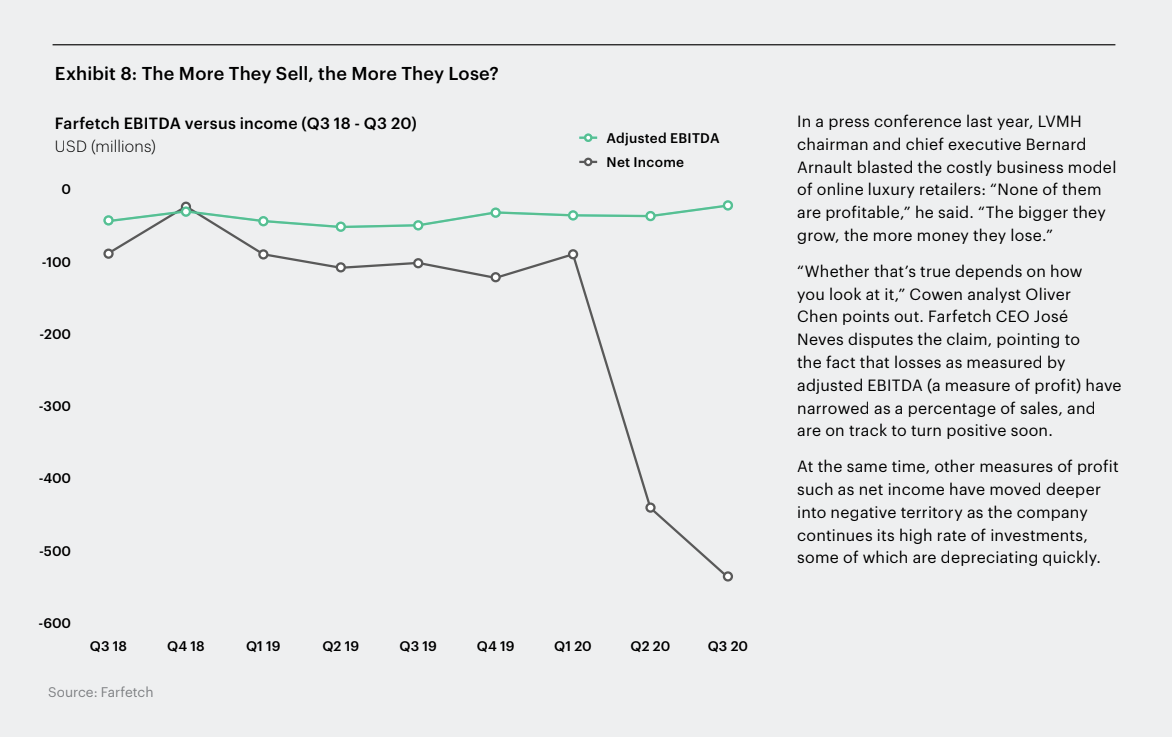

Chief executive José Neves has said the company would reach operating profitability (adjusted EBITDA) in the final quarter of 2020 and for the year overall in 2021. That means the company will need to maintain its improved bottom-line performance even as physical stores reopen, and as fashion companies find themselves competing for consumer dollars with restaurants, bars and travel again for the first time in almost a year. But adjusted EBITDA is only one measure of profit, and one whose use in the technology sector is sometimes criticised for the kinds of expenses it excludes. One-off investments in new technology, for example, are amortised over time and can be excluded from calculations of a company’s operating profitability, despite the fact that it is an ongoing, significant cost of business for these firms.

Fulfilling its promise to deliver positive adjusted EBITDA next year will reassure the market to some extent, but concerns about Farfetch continuing to spend more money than it makes might persist. Consolidation Ahead: After growing more than 50 percent this year, online sales of luxury products are expected to more than double by 2025, reaching more than $105 billion annually. But will the scale of demand justify the continued existence of so many players in the space? Some experts think not. “Consumers still like to shop an assortment, but all of this competition is eroding profitability for sure,” Bain analyst Claudia D’Arpizio said. “In this ecosystem we will likely have some consolidation, as well as more alliances and partnerships.” With a valuation of nearly $21 billion, and a well-demonstrated capacity for raising further investment funds when needed, Farfetch is well-positioned to benefit from further consolidation — either by making savvy acquisitions or by riding out the wave as competitors are pushed off the map.

Acquiring rivals, and their client lists with them, could allow Farfetch to broaden its base of consumers, and bolster its capabilities in areas where it lags behind rivals, such as brand-building and product curation. A potential combination of Farfetch and Richemont’s YNAP is currently the hottest subject of speculation, since the

Chief executive José Neves has said the company would reach operating profitability (adjusted EBITDA) in the final quarter of 2020 and for the year overall in 2021. That means the company will need to maintain its improved bottom-line performance even as physical stores reopen, and as fashion companies find themselves competing for consumer dollars with restaurants, bars and travel again for the first time in almost a year. But adjusted EBITDA is only one measure of profit, and one whose use in the technology sector is sometimes criticised for the kinds of expenses it excludes. One-off investments in new technology, for example, are amortised over time and can be excluded from calculations of a company’s operating profitability, despite the fact that it is an ongoing, significant cost of business for these firms.

Fulfilling its promise to deliver positive adjusted EBITDA next year will reassure the market to some extent, but concerns about Farfetch continuing to spend more money than it makes might persist. Consolidation Ahead: After growing more than 50 percent this year, online sales of luxury products are expected to more than double by 2025, reaching more than $105 billion annually. But will the scale of demand justify the continued existence of so many players in the space? Some experts think not. “Consumers still like to shop an assortment, but all of this competition is eroding profitability for sure,” Bain analyst Claudia D’Arpizio said. “In this ecosystem we will likely have some consolidation, as well as more alliances and partnerships.” With a valuation of nearly $21 billion, and a well-demonstrated capacity for raising further investment funds when needed, Farfetch is well-positioned to benefit from further consolidation — either by making savvy acquisitions or by riding out the wave as competitors are pushed off the map.

Acquiring rivals, and their client lists with them, could allow Farfetch to broaden its base of consumers, and bolster its capabilities in areas where it lags behind rivals, such as brand-building and product curation. A potential combination of Farfetch and Richemont’s YNAP is currently the hottest subject of speculation, since the

Swiss group invested $500 million in Farfetch in November. YNAP’s Net-a-Porter site maintains loyal clients, brand awareness and a knack for creating stimulating content online — all areas where Farfetch has lagged behind. But off-price division Yoox.com is contending with a serious backlog of old inventories, and its white-label unit that operates e-commerce for luxury brands behind the scenes has lost key clients in recent years, including luxury outerwear maker Moncler and Kering’s Saint Laurent and Balenciaga brands.

A strategic partnership between Farfetch, with its growing B2B division and more flexible back-end, and Net-a-Porter, with its strong brand identity, “would be an ideal way out for all parties concerned,” Bernstein analyst Luca Solca said. Tech Giants Waiting in the Wings: Farfetch must also contend with the ambitions of technology giants who, despite repeated fumbles breaking into the luxury space, are determined to crack the market. Amazon is persisting despite having long been perceived in the luxury industry as a “brand destroyer” — a company that pays little attention to how products are presented and is hell-bent on pushing down prices no matter what. “Its nature is to enforce commoditisation where convenience, selection and price win — not brand,” venture capitalist Lawrence Lenihan wrote in an op-ed published by The Business of Fashion.

In 2020, Amazon debuted a new platform, Luxury Stores, and has reportedly allocated $100 million to fund marketing for the venture. More than 150 million Prime subscribers worldwide who would benefit from one-day and same-day delivery on the site represent a key advantage for Amazon. Farfetch is watching Amazon’s movements closely. Amazon’s formidable resources and reputation for convenience and value represent a challenge, but Farfetch still sees them as a long way off from cracking the luxury market due to lower perception among both brands and consumers. Amazon has struggled to sign up major fashion brands who are very sensitive to this. “The main thing that brands need in this industry is an elevation of brand equity,” Neves said. “This is where the company DNA and the Amazon brand would need to evolve.” In a 2020 survey, just 8.4 percent of British customers saw Amazon as a premium destination, versus a 27.6 percent score for Net-a-Porter and 13.7 percent for Farfetch, according to WGSN’s.

Barometer, a consumer insights survey. Amazon's rise as a mass apparel broker has been fuelled by its edge in data, using unparalleled access to information on what consumers want and what they're willing to pay to reverse-engineer success stories, particularly from its white-label brands. That approach may not be transferable to the less commodified, more aspirational luxury fashion sector where consumers are buying into storytelling and heritage. Still, Amazon is launching Luxury Stores at a time when fashion brands have been weakened by the pandemic, and will be more susceptible to the company’s advances. Since launching with Oscar de la Renta as its only brand in September, the platform has signed on La Perla, Altuzarra, Roland Mouret and Elie Saab, among others. Even if Luxury Stores doesn’t take off on its own, Amazon could always acquire a company to marshall its unrivalled resources behind.

When it comes to M&A, “Amazon will have an appetite for this market,” D’Arpizio said. Facebook is another tech giant from outside the luxury space, which, despite not being known for dealing in physical goods, could start to chip away at Farfetch’s market. “Social shopping” — buying products discovered on sites like Facebook’s Instagram network, often completing the transaction without leaving the app — is estimated to have grown 20 percent to $23 billion in 2020, according to Emarketer.com. Instagram’s redesign, which highlights its shopping feature, is a sign that it’s seeking to expand its role in that value chain. Social shopping is already a major force in the Chinese market, where customers have rapidly grown accustomed to buying products directly from within the WeChat app — brands like Gucci, Burberry and Cartier are among those to sell directly from within the platform.

A strategic partnership between Farfetch, with its growing B2B division and more flexible back-end, and Net-a-Porter, with its strong brand identity, “would be an ideal way out for all parties concerned,” Bernstein analyst Luca Solca said. Tech Giants Waiting in the Wings: Farfetch must also contend with the ambitions of technology giants who, despite repeated fumbles breaking into the luxury space, are determined to crack the market. Amazon is persisting despite having long been perceived in the luxury industry as a “brand destroyer” — a company that pays little attention to how products are presented and is hell-bent on pushing down prices no matter what. “Its nature is to enforce commoditisation where convenience, selection and price win — not brand,” venture capitalist Lawrence Lenihan wrote in an op-ed published by The Business of Fashion.

In 2020, Amazon debuted a new platform, Luxury Stores, and has reportedly allocated $100 million to fund marketing for the venture. More than 150 million Prime subscribers worldwide who would benefit from one-day and same-day delivery on the site represent a key advantage for Amazon. Farfetch is watching Amazon’s movements closely. Amazon’s formidable resources and reputation for convenience and value represent a challenge, but Farfetch still sees them as a long way off from cracking the luxury market due to lower perception among both brands and consumers. Amazon has struggled to sign up major fashion brands who are very sensitive to this. “The main thing that brands need in this industry is an elevation of brand equity,” Neves said. “This is where the company DNA and the Amazon brand would need to evolve.” In a 2020 survey, just 8.4 percent of British customers saw Amazon as a premium destination, versus a 27.6 percent score for Net-a-Porter and 13.7 percent for Farfetch, according to WGSN’s.

Barometer, a consumer insights survey. Amazon's rise as a mass apparel broker has been fuelled by its edge in data, using unparalleled access to information on what consumers want and what they're willing to pay to reverse-engineer success stories, particularly from its white-label brands. That approach may not be transferable to the less commodified, more aspirational luxury fashion sector where consumers are buying into storytelling and heritage. Still, Amazon is launching Luxury Stores at a time when fashion brands have been weakened by the pandemic, and will be more susceptible to the company’s advances. Since launching with Oscar de la Renta as its only brand in September, the platform has signed on La Perla, Altuzarra, Roland Mouret and Elie Saab, among others. Even if Luxury Stores doesn’t take off on its own, Amazon could always acquire a company to marshall its unrivalled resources behind.

When it comes to M&A, “Amazon will have an appetite for this market,” D’Arpizio said. Facebook is another tech giant from outside the luxury space, which, despite not being known for dealing in physical goods, could start to chip away at Farfetch’s market. “Social shopping” — buying products discovered on sites like Facebook’s Instagram network, often completing the transaction without leaving the app — is estimated to have grown 20 percent to $23 billion in 2020, according to Emarketer.com. Instagram’s redesign, which highlights its shopping feature, is a sign that it’s seeking to expand its role in that value chain. Social shopping is already a major force in the Chinese market, where customers have rapidly grown accustomed to buying products directly from within the WeChat app — brands like Gucci, Burberry and Cartier are among those to sell directly from within the platform.

The China Opportunity:

The Chinese market will remain a key battleground for luxury players going forward. After brands made it easier for Chinese consumers to shop domestically, a process that was already underway before the pandemic, “consumers will get used to it and not travel outside just to buy luxury products,” said Arnold Ma, founder and chief executive of Chinese creative agency Qumin. Sales in mainland China are set to grow from just 11 percent of the luxury market in 2019 to as much as 28 percent in 2025, according to Bain. Fulfilling Farfetch’s China ambitions will require savvy management of partnerships with local tech giants to keep up with rapid changes in the market.

“China is moving very quickly into social commerce and live commerce. The biggest challenge for Farfetch is that the aggregator model will disappear,” Ma said. Farfetch has a partnership with WeChat-owner Tencent, but its model on the platform is still a “traditional e-commerce” one rather than something more interactive, he added. E-commerce giant Alibaba towers above Farfetch in terms of scale. Its quarterly revenues approached $23 billion in the third quarter of 2020, versus $438 million for Farfetch. And where Amazon has yet to break into luxury, Alibaba already has nearly 200 luxury designer brands including Prada and Cartier on Tmall’s Luxury Pavilion spin-off site. Being an investor in Farfetch’s joint venture will not slow down their own efforts to expand their grip on luxury e-commerce in China.

“Alibaba are the kings in this market. I would be sceptical regarding how much value they’ll actually be willing to leave with Farfetch, or for how long,” said e-commerce consultant Michel Campan. “They’ll be watching and learning to figure out how to do what Farfetch does themselves.” But even if Farfetch isn’t in a position of strength vis-à-vis China’s e-commerce giants long-term, making thousands of SKUs readily available online in the country for the first time could be a unique enough proposition to take advantage of growing interest in niche brands that help fashion-focused youngsters stand out from their peers. Farfetch will need to nail the landing when they launch on Tmall, with strong branding and top-notch service that can generate a positive buzz from day one. “Real-time word-of-mouth has always been, culturally speaking, something that is valued more than just what a brand says it’s doing,” said Iris Chan, partner and international client development director at Digital Luxury Group.

The Tipping Point Towards Big Promises: Farfetch says its mission is to become the “global platform for luxury fashion,” and its new investor Richemont has decided to support it in that bid. In a November press conference, chairman Johann Rupert said he wants it to become the sector's “neutral platform” to share cost and centralise expertise on a range of digital issues that remain outside brands’ core competency of designing and marketing products. While the biggest groups like LVMH and Kering have said they prefer to create in-house technologies, hundreds of brands in the fragmented sector remain outside their control. Digital has become their top priority, and few of them can do it on their own.

The Chinese market will remain a key battleground for luxury players going forward. After brands made it easier for Chinese consumers to shop domestically, a process that was already underway before the pandemic, “consumers will get used to it and not travel outside just to buy luxury products,” said Arnold Ma, founder and chief executive of Chinese creative agency Qumin. Sales in mainland China are set to grow from just 11 percent of the luxury market in 2019 to as much as 28 percent in 2025, according to Bain. Fulfilling Farfetch’s China ambitions will require savvy management of partnerships with local tech giants to keep up with rapid changes in the market.

“China is moving very quickly into social commerce and live commerce. The biggest challenge for Farfetch is that the aggregator model will disappear,” Ma said. Farfetch has a partnership with WeChat-owner Tencent, but its model on the platform is still a “traditional e-commerce” one rather than something more interactive, he added. E-commerce giant Alibaba towers above Farfetch in terms of scale. Its quarterly revenues approached $23 billion in the third quarter of 2020, versus $438 million for Farfetch. And where Amazon has yet to break into luxury, Alibaba already has nearly 200 luxury designer brands including Prada and Cartier on Tmall’s Luxury Pavilion spin-off site. Being an investor in Farfetch’s joint venture will not slow down their own efforts to expand their grip on luxury e-commerce in China.

“Alibaba are the kings in this market. I would be sceptical regarding how much value they’ll actually be willing to leave with Farfetch, or for how long,” said e-commerce consultant Michel Campan. “They’ll be watching and learning to figure out how to do what Farfetch does themselves.” But even if Farfetch isn’t in a position of strength vis-à-vis China’s e-commerce giants long-term, making thousands of SKUs readily available online in the country for the first time could be a unique enough proposition to take advantage of growing interest in niche brands that help fashion-focused youngsters stand out from their peers. Farfetch will need to nail the landing when they launch on Tmall, with strong branding and top-notch service that can generate a positive buzz from day one. “Real-time word-of-mouth has always been, culturally speaking, something that is valued more than just what a brand says it’s doing,” said Iris Chan, partner and international client development director at Digital Luxury Group.

The Tipping Point Towards Big Promises: Farfetch says its mission is to become the “global platform for luxury fashion,” and its new investor Richemont has decided to support it in that bid. In a November press conference, chairman Johann Rupert said he wants it to become the sector's “neutral platform” to share cost and centralise expertise on a range of digital issues that remain outside brands’ core competency of designing and marketing products. While the biggest groups like LVMH and Kering have said they prefer to create in-house technologies, hundreds of brands in the fragmented sector remain outside their control. Digital has become their top priority, and few of them can do it on their own.

Further Reading

• GQ, Farfetch Wants to Be the Netflix of Fashion

• The New York Times, The Luxury E-Commerce Wars Heat Up

• The Business of Fashion, Why Is Everyone Betting on Farfetch?

• The Business of Fashion, How the Farfetch-Alibaba-Richemont Alliance Could Change the Game in the World’s

Largest Luxury Market

• The Business of Fashion, What the Farfetch-Alibaba-Richemont Mega-Deal Means for Luxury E-Commerce

• The Business of Fashion, Five Years After the Farfetch Deal, What’s Next for Browns?

• The Business of Fashion, Are Online Marketplaces the New Department Stores?

• The Business of Fashion, Farfetch’s Latest Ad Campaign Sells a New Product: Itself

• The Business of Fashion, Farfetch Sales Soared During Lockdowns

• The Business of Fashion, The BoF Podcast: Farfetch’s José Neves Says Profitability Is Still Possible in 2021

• The Business of Fashion, The Problem With the Online Luxury Model

• The Business of Fashion, Case Study: The Next Wave of Luxury E-Commerce

• The Business of Fashion, Farfetch Sees Path to Profitability — in 2021

• The Business of Fashion, A Cloudy Picture at Farfetch

• The Telegraph, Falling apart at the seams: Why fashion darling Farfetch’s value plummeted by $2bn

• Quartz, Farfetch’s first year as a public company has not gone well

• The Business of Fashion, Why Farfetch Bought New Guards Group

• The Business of Fashion, Why Farfetch’s Free-Spending Ways Have Some Investors Concerned

• The Business of Fashion, Farfetch Surpasses $8 Billion Valuation in Early Trading

• The Business of Fashion, Inside Farfetch’s Store of the Future

• The Business of Fashion, Farfetch’s Global Platform Play

• The Business of Fashion, Who’s Winning the Fashion E-Commerce Race?

• The New York Times, The Luxury E-Commerce Wars Heat Up

• The Business of Fashion, Why Is Everyone Betting on Farfetch?

• The Business of Fashion, How the Farfetch-Alibaba-Richemont Alliance Could Change the Game in the World’s

Largest Luxury Market

• The Business of Fashion, What the Farfetch-Alibaba-Richemont Mega-Deal Means for Luxury E-Commerce

• The Business of Fashion, Five Years After the Farfetch Deal, What’s Next for Browns?

• The Business of Fashion, Are Online Marketplaces the New Department Stores?

• The Business of Fashion, Farfetch’s Latest Ad Campaign Sells a New Product: Itself

• The Business of Fashion, Farfetch Sales Soared During Lockdowns

• The Business of Fashion, The BoF Podcast: Farfetch’s José Neves Says Profitability Is Still Possible in 2021

• The Business of Fashion, The Problem With the Online Luxury Model

• The Business of Fashion, Case Study: The Next Wave of Luxury E-Commerce

• The Business of Fashion, Farfetch Sees Path to Profitability — in 2021

• The Business of Fashion, A Cloudy Picture at Farfetch

• The Telegraph, Falling apart at the seams: Why fashion darling Farfetch’s value plummeted by $2bn

• Quartz, Farfetch’s first year as a public company has not gone well

• The Business of Fashion, Why Farfetch Bought New Guards Group

• The Business of Fashion, Why Farfetch’s Free-Spending Ways Have Some Investors Concerned

• The Business of Fashion, Farfetch Surpasses $8 Billion Valuation in Early Trading

• The Business of Fashion, Inside Farfetch’s Store of the Future

• The Business of Fashion, Farfetch’s Global Platform Play

• The Business of Fashion, Who’s Winning the Fashion E-Commerce Race?

Editor’s Note: This case study was corrected on January 15, 2021.

A previous version of this report stated that Farfetch’s Store of the

Future team is working with Chanel to implement a service for

shipping items purchased in-store. This is incorrect. Chanel does

not have this Store of the Future functionality enabled.

A previous version of this report stated that Farfetch’s Store of the

Future team is working with Chanel to implement a service for

shipping items purchased in-store. This is incorrect. Chanel does

not have this Store of the Future functionality enabled.